By 1934, when the Polish publisher Republika in Łodz released Essad Bey’s two pulp novels, he had already produced a notable number of texts. Between 1926 (aged 21) and 1933 Essad Bey had contributed more than 160 articles to Willy Haas’s literary magazine Die literarische Welt. His first book appeared in the winter of 1929/1930 when he was 24 years old. It was his satirical quasi-autobiography Blood and Oil in the Orient in which he “fabulated” about his childhood in Baku and his adventurous flight from the Bolsheviks. Between this book and the two pulp novels or novellas, eight more books of his were published – among them the biographies Stalin and Mohammed, two books about the Caucasus, three about Russia and one about petroleum. This places the novellas half-way between his autobiographical debut and his timeless masterpiece Ali and Nino, which was published 1937 under the pseudonym Kurban Said.

We don’t know anything about the rediscovery of “Manuela” and “Love and Petroleum” but we can assume that Professor Gerhard Höpp (†2003) of Zentrum Moderner Orient in Berlin found them by way of a worldwide routine search in library catalogues. He had begun investigating Essad Bey’s life in the early 1990s. Up to the point of Höpp’s discovery, their existence was totally unknown. And to date nothing else has come to light about them, no manuscripts, no correspondence – except perhaps a casual remark found in the autobiography of Essad Bey’s literary agent Karl Frucht (Hertha Pauli’s business partner), namely that “we successfully sold some of his adventurous short stories”.2 Since so far nothing is known of other “adventurous short stories”, Karl Frucht might indeed speak of the two novellas.

Simply structured and narrated, these stories don’t seem to fit seamlessly into Essad Bey’s literary oeuvre, at least not at first sight. And yet, these two “penny dreadfuls” doubtlessly are genuine “Essad Beys” because an “Essad Bey” contains the very life-themes of the author himself: petroleum, which he first had narrated in Twelve Secrets in the Caucasus (1930), with the difference that he puts the plot to the service of the Portuguese revolution. Last but not least, he’s combining two big financial scandals of 1925 and 1929/30.

Alone these references to world history, into which Essad Bey puts his protagonists, distinguish the two novellas from regular pulp novels. This is important to note, because they have been criticized as “simplistic and primitive …” and having “… cheap, sensational plots. His protagonists are involved with the dark world of intrigue, seduction, blackmail and revenge in their quest to acquire big money and power.”3

Let’s not forget that these stories are just that: dime novels written for that Polish series of weekly pulp fiction.

Now let’s look at some details of the plots of “Manuela” and “Love and Petroleum”.

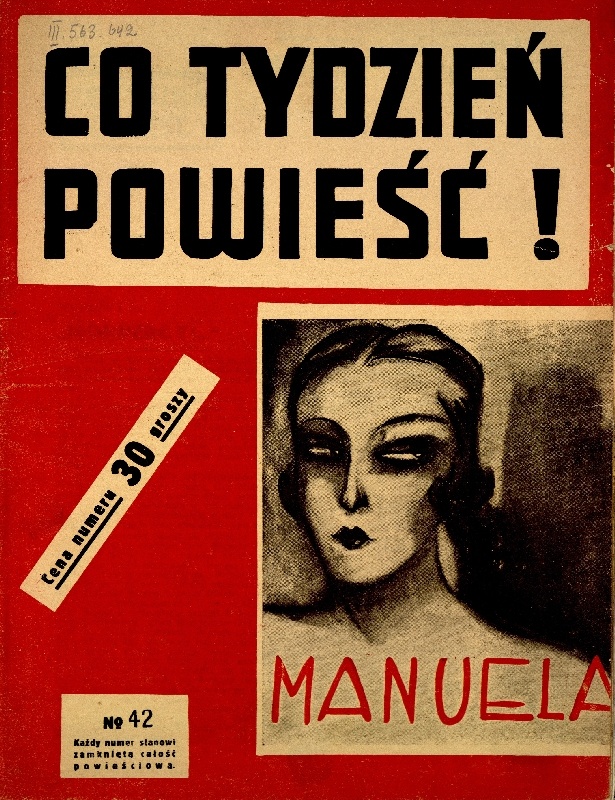

“Manuela”

Price for this issue 30 Groszy

Nr. 42

Each issue is a complete story

The backdrop of this story is Portugal before the military coup of 1926, during the time of political instability and frequently changing governments. A few revolutionaries want to overthrow the government. They are coming up with the daring plan of emitting large quantities of legally printed banknotes in order to unleash an inflation, which might in turn upset the population against the government. The heroine of the novel is the young and pretty Manuela Letão. She supports the revolutionaries in order to avenge her father who was a former general. By clever and witty moves the revo- lutionaries manage to convince the British money printers that they are official envoys of the Bank of Portugal and fully authorized to order a series of banknotes. In many ludicrous (and sometimes not very convincing) ways these banknotes are being released into the market. Among them: Manuela, the main protagonist, shops in Paris “till she drops”.

As a result the Portuguese Escudo and economy deteriorate and the government is indeed overthrown.

Into this story Essad Bey has built the following historical incidents:

The real banknote scandal by which the Portuguese economy collapsed on account of large amounts of real bank notes took place in 1925. A certain Alves dos Reis (1898–1955) succeeded in convincing the British bank note printers Waterlow & Sons Ltd.,

whose client the Portuguese National Bank had been for years, that he was authorized to order 200,000 banknotes of 500 Escudos each (see illustration above). Once this large number of legally printed bank notes circulated in the market they had a disastrous effect on the economy. The loss of reputation of the Portuguese government and currency was immense. In the real case of Alves dos Reis the printers Waterlow & Sons Ltd. had to pay compensation to Portugal and, as a result, had to file for bankruptcy. In “Manuela”, however, the revolutionaries have “noble” motives and the story has a happy-end: the printers are discharged as not guilty and the blame is put on Portugal.

The motives of the real Alves dos Reis were simply power and personal gain4. It is likely that he was ignorant of the effect these bank notes would create. But Essad Bey’s protagonists know better – no wonder, the novel was written nine years after the real scandal. For them it is easy to submit their cause selflessly to the revolution.

That “good” motive Essad Bey had borrowed from another money-forgery scandal which caused international headlines in 1930 and was called the “Chervonets Affaire”.

“Chervonets” was the denomination of the currency used in the Russian empire and then by the Soviets until 1947. Revolutionaries from Georgia/Caucasus had produced in Germany a large quantity of Chervonets banknotes, which they wanted to circulate in the Soviet-ruled Caucasus. They were hoping to undermine the Soviet economy. It is thinkable that the Alves dos Reis scandal and its effect on Portugal had given them the idea. But their plan failed, German police discovered the banknotes in a warehouse in Frankfurt before they could be dispatched, and the forfeiters were brought to trial. The Chervonets trial took place in Berlin-Moabit in 1930 and Essad Bey took part in it as a journalistic observer.5 At first, the money forgers were lucky: the German court discharged them on the grounds of the newly-passed „Reichs-Amnestie“ for political offendors. Due to the protest of the Soviet Union in 1938 a revision was held in 1930 and the forgers were sentenced to prison for two years, respectively two years and 10 months.6

As mentioned above, Essad Bey used a robbers’ tale in “Manuela” which he had first written down in his Twelve Secrets of the Caucasus: By pretense all policemen and soldiers were lured out of the Daghestanian city of Kislar and a gang of robbers mugged the whole city, including all private households, the bank and the post office. To delay the robbers’ discovery, all inhabitants of the city were forced to strip naked and were left behind without clothes. Supposedly this robbery was organized by a certain Kamo, a comrade of Stalin, to support Lenin, then still in Switzerland, with the loot. In “Manuela” the Portuguese revolutionaries use the same trick.

* * *

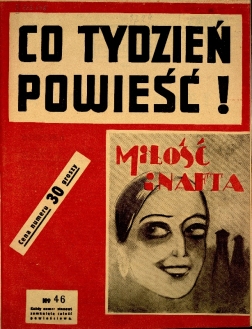

“Love and Petroleum”

Nr. 46

Each issue is a complete story

After an adventurous escape from the Bolsheviks in Batumi, the Georgian princess Tamara stands on the streets of Paris. Just when she’s fainting of exhaustion the attractive Vano catches her before she hits the ground. Vano proves to be Tamara’s compatriot. He takes her to the mysterious Armenian Petros Petrossian who is a business tycoon. Petrossian exploits Tamara in his battle against the Bolsheviks by matchmaking her to Sir Richard King, a petroleum tycoon. Petrossian hopes that King, through his love for Tamara, might be moved to help fight for the liberation of Tamara’s home country – and, by that, regain access to the Caucasian oil fields.

The author has used the following autobiographical details and historical personalities:

Essad Bey surely named the Georgian princess Tamara Alaschidse not only after the legendary Queen Tamara (1160–1230), but also after his favorite aunt Tamara, the younger sister of his mother Bertha, with whom he was very close, since they were only twelve years apart.

Like Princess Tamara’s route of escape, Essad Bey and his father went from Georgia to Turkey – not alone in a little sail boat like the girl, but first class in a luxury liner, where the waiters proclaimed, that “after the departure from Georgian waters all prices are to be understood in gold.”7

Arriving in Istanbul, the Nussimbaums resided in Turkey’s first international luxury hotel, the Pera Palas, which was built in 1892 particularly for the passengers of the then-new Orient Express. Princess Tamara only sold matchsticks in front of that hotel. In one short sentence Essad Bey describes how the girl felt for the city: “For her Constantinople was a dream” – and in truth he’s speaking of himself. In his last (yet unpublished) manuscript Essad Bey – or in this case rather “Kurban Said” – describes vividly what that city meant to him: “I can hardly recall the feelings of that distant boy who walked, almost staggering of bliss, through the streets of the Caliph’s city and visited the mosques.”8

For both the writer and the novel’s character, Princess Tamara, Constantinople was just a stop-over on the way to Paris, the “capital of the world”. There Essad Bey and his father stayed with rich relatives from his mother’s side, “in a large house on the Champs Elysees”9 – the Hotel Windsor10. In his last manuscript Essad Bey describes his Paris wanderings and his insights into the life of the poor immigrants. During this time (Lev was about 15 years old) he also must have learnt about the high-finance and politics around petroleum. Like other oil-well owners, father Nussimbaum was able to sell “dead souls” – i.e. the ownership documents of their Caucasian oil wells – to Shell, Standard Oil and other investors. This was possible because the whole Western world believed that the “spook of the Bolsheviks” would disappear within a year. (This notion, which proved to be wrong, was the reason why virtually none of the oil millionaires considered cutting back expenses and many of them ended-up as taxi drivers or worse.) By way of selling the “dead souls” the Nussimbaums were able, at least for a while, to keep-up their luxurious life-style.11

In 1921 father and son Nussimbaum settled in Berlin where their money soon ran out. The deeply despairing feeling of being uprooted shines through when Essad Bey writes in “Love and Petroleum”: “They say a refugee’s bread is bitter. This is not true. A refugee’s bread is neither bitter nor sweet, because the exile has no bread to offer to the refugees.”12

Princess Tamara’s destiny takes a happy turn when she marries the petroleum tycoon Richard King. In Essad Bey’s own life, petroleum is connected rather to tragedy. Only after 1930, with the success of his quasi-autobiography Blood and Oil in the Orient his own destiny took a happy turn. Before the two novellas were written, Essad Bey’s Flüssiges Gold (“Liquid Gold”), which is the “biography of the global power petroleum”, was published in 1933. It was among his most successful books until the war broke out in 1939. In a way petroleum and Essad Bey stayed faithful to each other. Looking at the publishing dates and cross-references of Flüssiges Gold and the novellas one can easily see that Essad Bey recycled some of the big book’s material into the thin ones.

Essad Bey’s homesickness to the Caucasus shines through in Princess Tamaras dreams of her green Georgian homeland. Surely Essad Bey had an emotional connection to Georgia, where his father was born in 1873 and where his parents had married in October 1904.

Next to these autobiographical traces we find in “Love and Petroleum” persons from the economical history of petroleum and their doings. Indeed, Essad Bey’s protagonists Tamara Alaschidse, Richard King and Petros Petrossian have their real-life models. Tamara’s was Lydia Pawlowna, a Russian-Caucasian immigrant, and, as Tamara, a general’s daughter. She was the wife of Sir Henry Wilhelm August Deterding (1866–1939), founder and main shareholder of Royal Dutch Shell, who was, in turn, the model for Richard King. Sixty per cent of the Caucasian oil wells belonged to Deterding, and as in Essad Bey’s novel, he met his wife Lydia Pawlowna in the salon of an obscure finance expert – Calouste Gulbenkian – whose name in the novel is Petros Petrossian.

Calouste Gulbenkian (1869–1955) was born and raised in Turkey. He was of Armenian descent and a financial expert, petroleum researcher and art collector who managed to position himself as an unavoidable negotiator in the worldwide petroleum industry and accumulated legendary wealth. Between 1915 and 1942 he lived – like Petrossian – in his house at the Etoile in Paris. And as in the novel, Gulbenkian and Deterding were at odds with each other over the question of the Soviet oil. Just like in the novel, also in real-life Gulbenkian unleashed the stock exchange intrigue against Shell. 13

However, the Petrossian in the novella does not have much likeness to his real-life model Gulbenkian. Essad Bey attributes character traits to him, which, according to his book Flüssiges Gold, were known of John D. Rockefeller – i.e. the daily reading of the Bible and of the stock exchange reports. The reason for this might be that such details were readily available about Rockefeller but not about Gulbenkian.

In “Love and Petroleum” we find three sentences about Richard King which are not explained and don’t seem to be connected to the story:

“Richard King and the Forgers” (German page 34);

“Richard King was the only man on earth whose name one could be read in the newspapers in the same sentence with money forgers without having this harm him” (German page 35);

“Richard thought about the money-forgers who were always mentioned together with his own name” (German page 39).

These clearly are hints to the “Chervonets trial” in Berlin which Essad Bey visited as a journalistic observer, as described further above. In that trial the two defendants Karumidse and Sadatheraschwili claimed that Sir Henry Deterding, founder and main shareholder of Royal Dutch Shell, had financed the preparations for the Chervonets forgery. Deterding was one of the richest people on earth at the time and known to be a dedicated enemy of the Bolsheviks. It surely was in his interest to overthrow the Soviet regime in order to regain access to his Caucasian oil fields. Deterding, or course, denied any connections to the forgers.

That the above listed three sentences are not connected to the rest of the story was perhaps a result of Essad Bey’s quick way of writing. The Polish translator did obviously not stumble over them.

The real-life model for Richard King, Henry Deterding was a Dutchman. In 1920 he became a honorific Knight of the British Empire for his contribution to Dutch-British relations. He moved the headquarters of his company Royal Dutch Shell from Amsterdam to London – most likely to have the British military as a rear cover especially in his competition with Rockefeller’s Standard Oil and the conflicts connected to that overseas.14

Just by the way I would like to mention that Deterding was a great sympathizer of the Nazis in Germany (perhaps because they opposed the Bolsheviks) and he supported them with many millions from his own pocket. In 1937 he supposedly donated 70 million Reichsmark to the Winter Emergency Relief Fund in Germany. He owned a manor in the province of Mecklenburg. Hitler sent a mourning wreath to Deterding’s funeral in 1939.15

* * *

Looking at Essad Bey’s oevre, these two pulp novels surely hold their own position. But with their historical references, their characteristic way of portraying people, their dense, adventurous plots they surely bear Essad Bey’s handwriting. This makes these two accidental finds a rewarding discovery, not only for Essad Bey fans.